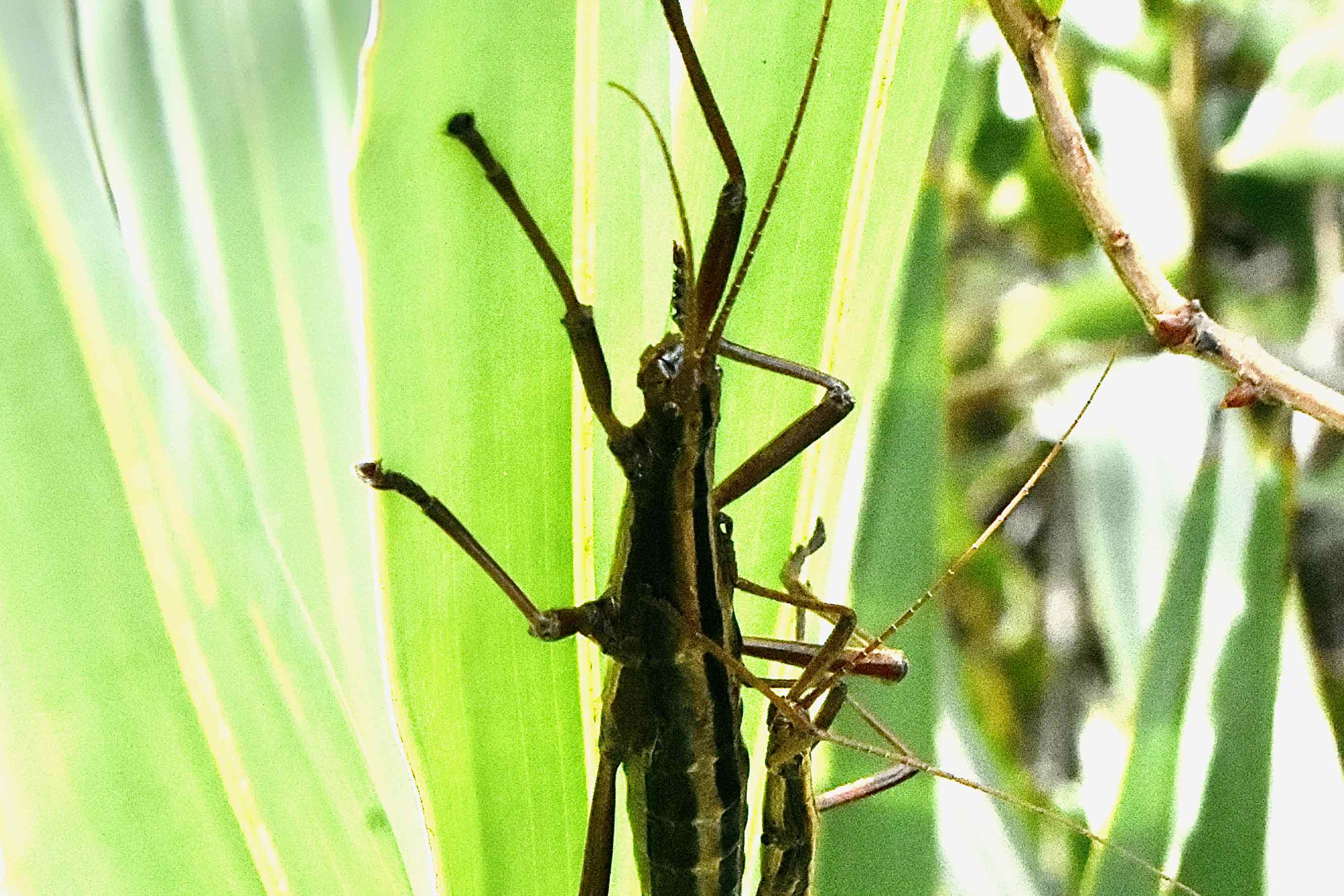

Two-striped walking stick, aka southern two-striped walking stick, photographed at Pondhawk Natural Area, Boca Raton, Palm Beach County, in November 2019.

Size matters for male two-striped walking sticks. Just not in the way we might think.

They are much smaller than the ladies of the species, and from an evolutionary standpoint, smaller is actually better in male walking sticks. Smaller means quicker maturation, and quicker maturation means a having a better shot at finding a female mating partner and passing on one’s genes.

Be a little late to the party, so to speak, and the guys of the species might find themselves on the outside looking in. That’s especially so, because there are far more males than females, so the competition to breed is fierce.

Female two-striped walking sticks, Anisomorphora buprestoides, on the other hand, are among the larger insects found in the United States. From an evolutionary standpoint, larger females have the advantage of carrying more eggs, meaning more offspring and a greater chance of passing on their genes.

Males go an average of about 4.1 centimeters long, a little more than an inch-and-a-half, while females average 6.7 centimeters, a little more than two-and-a-half inches long. They can grow as large as 8 centimeters, more then 3 inches.

Females are not only longer than the guys, they’re also thicker, heftier. The reason is an odd behavior that two-striped walking sticks have.

The two sexes are often seen together, the male riding on the back of a female, so often, in fact, that it’s rare to see a lone female. The piggybacking can go as long as three weeks during which the two mate, off and on. Even when not mating, the two stick (pun unintended) together in this strange ride.

There is another side to this mating behavior and that is defense. Walking sticks have no wings and are on the slow side otherwise.

Camouflage is their first line of defense — they’re called walking sticks for a reason. But once spotted by a bird, a spider, an opossum, an ant, what are these seemingly perpetually mating bugs to do? Getting out of Dodge quickly isn’t an option and they might be a tad distracted by what they're doing and unaware of pending danger.

A quick and easy meal, two for the price of one? Maybe not.

Walking sticks have a second, rather nasty line of defense: chemical warfare. They have two sac-like glands on the side of the thorax, just behind the head, that secrete a stinky, irritating chemical called anisomorphal. (For you chemistry fans out there, anisomorphal is a terpene dialdehyde that’s related to catnip, oddly enough.) A walking stick can shoot the stuff two to three feet with precision at anything accosting or threatening it.

When there are two of them together, that’s twice the firepower, twice the defense. The stuff stinks and it burns when it hits the eyes, mouth or nose of the would-be attacker. It can cause temporary blindness.

Oh and walking sticks are able to defend themselves this way even as nymphs from the time they hatch.

The defense has its limits, though. A large female two-striped walking stick can shoot up to five bursts, but then is depleted and require as long as two weeks to recharge. A male might have two bursts in him.

More basics:

Two-striped walking sticks are light brown with prominent striping. There are two other color forms, black and white found in the Ocala area, and orange found in the vicinity of the Archbold Biological Station in Central Florida. The brown form is most prominent throughout the two-striped walking stick range.

It is the most common walking stick species found in Florida. Its range extends along the Atlantic and Gulf coastal plains from South Carolina west to Texas.

Note: Our guy is often called the southern two-striped walking stick to distinguish him from a similar-looking cousin, scientifically known as Anisomorpha ferruginea, the northern two-striped walking stick. The northern, which is smaller and paler, is not found in Florida.

Two-striped walking sticks are herbivores. They’re known to feed on scrub oaks and etonia palms, but generally don’t assemble in large enough numbers to seriously damage the plants that they’re munching on.

They’re also nocturnal feeders, spending the daytime hours as out of sight as possible.

Parental care is minimal, as one might expect. Females simply drop their eggs onto the ground from whatever plant they happen to be on. The black-and-white Ocala form goes a step further, digging a hole with her front and middle legs, arching her abdomen and ovipositor over her body and head and depositing eight to ten eggs into the pit. She’ll cover the hole and repeat the process several times. That’s it.

Two-striped walking sticks are most abundant in the fall, and that’s when most eggs are deposited. The nymphs are green, and as mention above, have the ability to protect themselves chemically.

One more note: if you get squirted in the eyes by a walking stick, first aid is to wash them out for 15 minutes. A trip to the emergency room is recommended and a visit to an opthalmologist might be necessary if vision is impaired. Symptoms last anywhere from two hours to 10 days. Generally, though, there is full recovery within five days.

How painful is the experience? The victim in an often-cited case in Texas from 1932 likened the sensation to “molten lead.”

The American Academy of Opthalmology says there are no recorded cases of anyone going blind from walking stick juice, but it is possible.

Two-striped walking sticks are also known as devil’s riding horse, prairie alligator, witch’s horse, devil’s darning needle, scorpion or musk mare. They are members of Pseudophasmatidae, the walking stick family.

Pondhawk Natural Area